The only thing that matters is how a character transforms over time.

This is Part 1 of my Four-Part Miniseries on how to PLAN, WRITE, EDIT, and PUBLISH your creative work.

This episode is a deep-dive into the fundamentals of storytelling, fundamentals that apply to any genre and any medium.

My co-host for the series is Greg Larson, who first came on the pod in August with great advice on how to market your book.

Greg, author of Clubbie: A Minor League Baseball Memoir, was a fantastic resource as I finished and published my memoir Zen and the Art of Coaching Basketball.

In this episode, Greg and I dive into the questions and process you should have in place before you start writing.

We discuss many genres of story, from sci-fi to memoir to zombie apocalypse, and many types of story, from prose to screenplay to film.

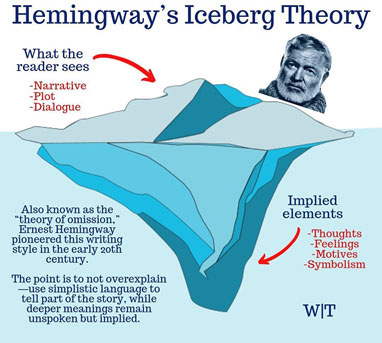

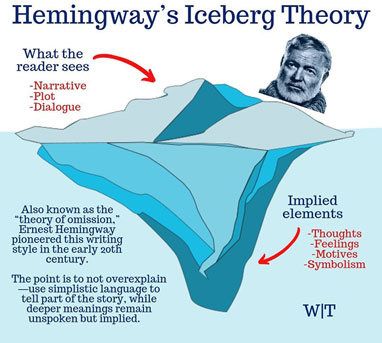

We touch on the Iceberg Theory by that old hack Ernest Hemingway.

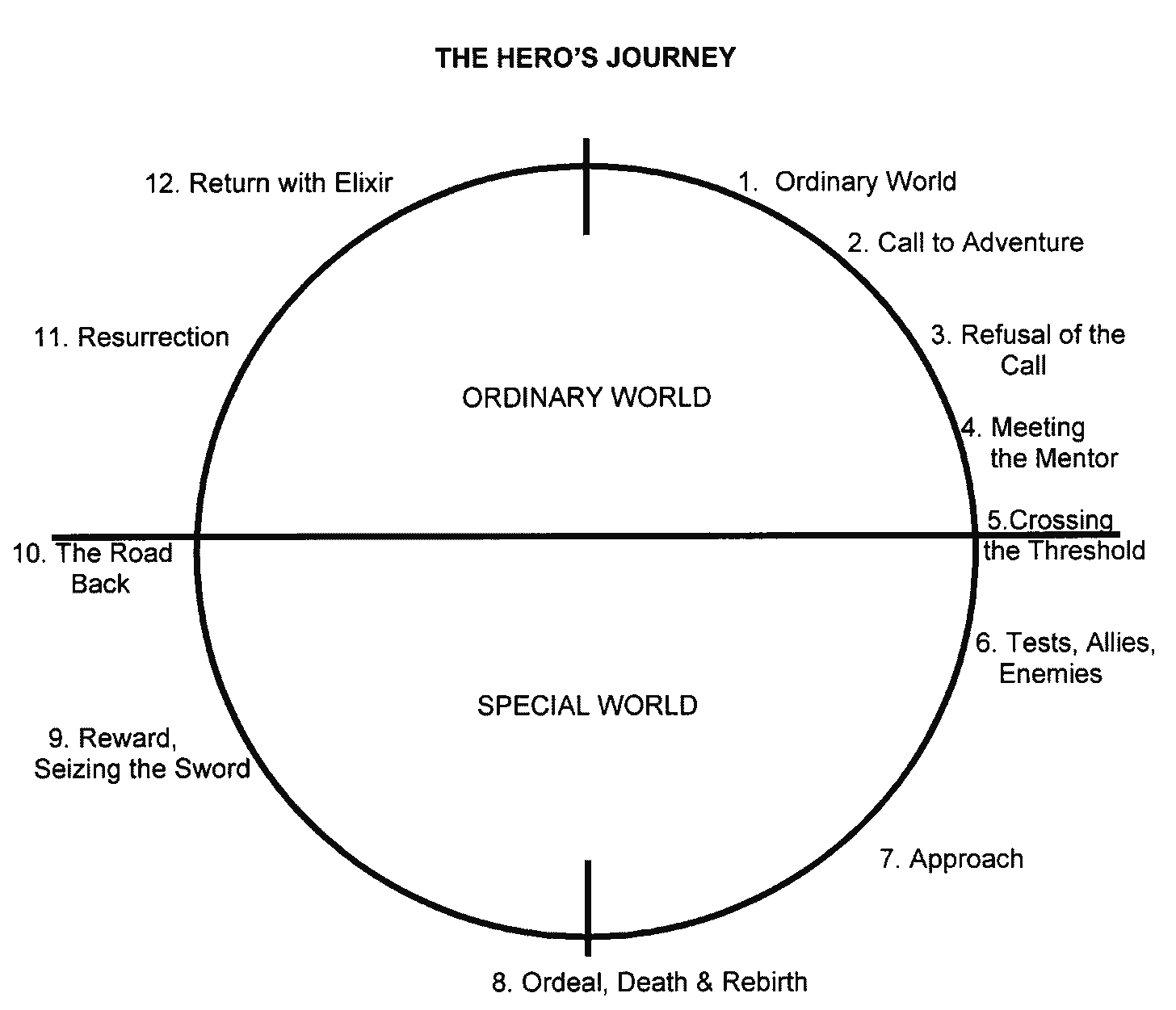

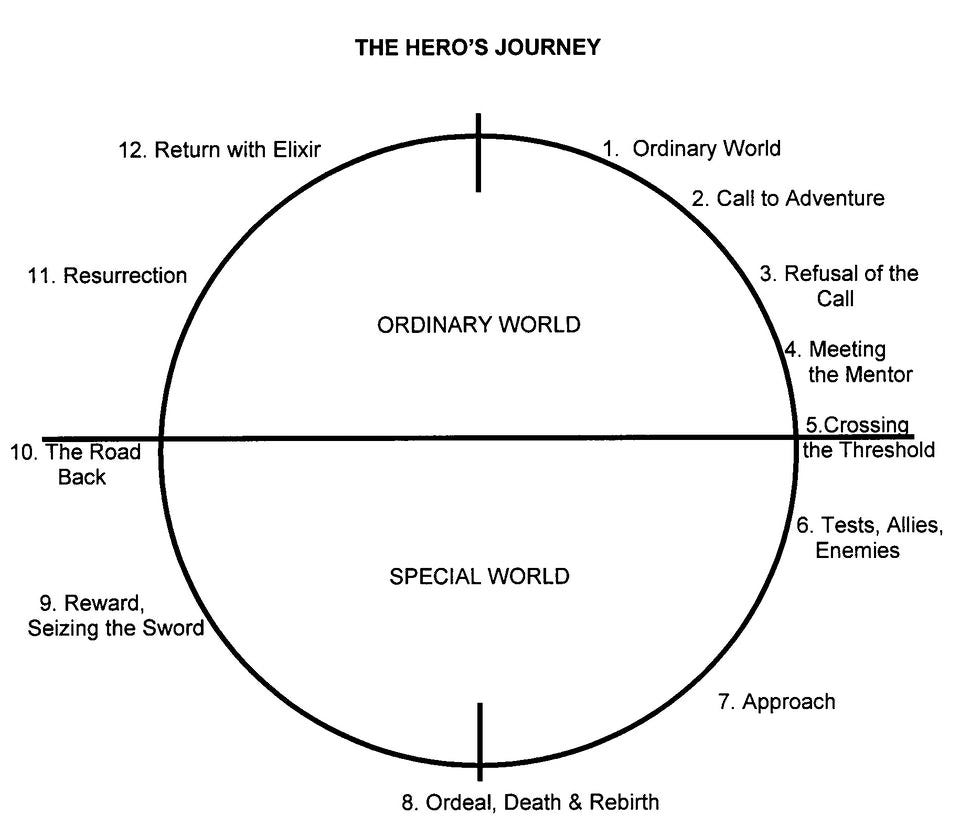

And The Hero’s Journey, based on the work of Joseph Campbell.

We talk how to find your theme, create character backstory, and outline.

At the end of Part 1 Greg shares his process for ensuring he finishes his book.

It’s genius.

And involves BBQ.

Part 2 will focus on Writing, Part 3 on Editing, and Part 4 on Publishing.

It is our hope that these four episodes will provide a guide for you to publish your work.

Please share with the storytellers in your life and, more importantly, the people who have a story to tell.

Speaking of telling a story, this mini-series is sponsored by Greg’s company, Self-Publishing Sherpa. If you like our conversation and wish to engage Greg and his group, please schedule a free strategy call.

Last but not least, I’m adding two new features to the podcast with this episode (at least for this mini-series): Transcripts and YouTube video :-)

Episode Transcript

Ben Guest:

Planning obviously is the beginning of the creative process. Greg, what are your thoughts about planning?

Greg Larson:

In general, I think a lot of authors get stuck in the planning stage. What I find is people try to make a perfect outline. For example, when I advise people in non-fiction, my entire thought process is, just create an outline that will remind you what you need to write in two months. That's it. Don't write your book in the outline, none of that kind of stuff. But even before you get into the outline, figuring out who your audience is, figuring out who your ideal reader is in that audience, figuring out what your goals with the book are, and figuring out how you want your reader to change. This is more strictly nonfiction, but figuring out how you want your reader to change, those are incredibly important aspects of the planning process that I think a lot of people overlook.

Ben Guest:

Let's start there and let's start with nonfiction and we'll probably jump over to fiction as well at some point, but we'll try to signpost that. So in nonfiction, I think the key question to ask yourself at the beginning is what you just said, "Who is this written for?" And I think the mistake a lot of people make is, I had an interesting experience or I've had an interesting life, or I had an interesting business, or I met this person or whatever. It's great that it's interesting to you. If you want to write that down for your kids, for your family, for your best friend, great, do that. But in terms of connecting to someone who doesn't know you and has no connection to you, you have to ask, "Who is this for?" Tied to that, "What do I want them to get out of it?"

Greg Larson:

A book with no audience is a diary, which is purposely fine and valid, but it doesn't need to be published as a book necessarily. The way I think about it, especially with memoir, a lot of people think that a memoir is a series of things that happened. Do you ever hear somebody tell you a story and they just go through every single detail, they're like, "Well, what was the cashier's name? I forget what they... or the week it was." None of details matter. They're not relevant. The only thing that matters is how a character transforms over time and the story that gets them to transform. So when you look back through your life and you're interested in writing a memoir about it, you have to think, "What is the shortest period of time in which I had the greatest transformation?" That is how you answer that so-what question for the reader, I think. Once you're able to put a timeframe on it, even if you're not writing a memoir, any kind of nonfiction where you have personal stories inside of it, once you have a tight timeframe around it of, "I started out as a new clubhouse attendant in a minor league baseball team and I ended as a grizzled veteran." Boom, I have a constrained timeframe that I can work with.

Ben Guest:

So we're talking about both a compressed time frame, and as importantly, the greatest amount of change that happened in that compressed timeframe?

Greg Larson:

That is what makes the most compelling stories, I believe.

Ben Guest:

We talk about storytelling traditions, and if we go back to Aristotle and Poetics, it's unity of time, place and action, everything should happen over three days and two nights. I'm a big fan of the film director, Michael Mann, who did Heat and Miami Vice and Last of the Mohicans. And he's like, basically you want your story to be the most important few days, few weeks, few months, whatever it is, of your hero's life. It is the key moment of their adult life or even their childhood, what happened in those moments that changed them. And in that specific detail, it'll become relatable.

Greg Larson:

Yes. Yeah, exactly. A lot of authors, they'll try to become universal by being vague or not trying to exclude anybody with too many details. It's like, no, the universality is found in specifics.

Ben Guest:

Right. And so just to highlight this for the listener, we just said earlier, remember how you hear a boring story and the person tells you every little detail? So that's a story with too much information. The flip side of that is once you've nailed down the timeframe, and once you've nailed down the experience, now you want as much specific detail as possible and not to go, “Well, it needs to be more general so people can relate.” For some reason, the way we're wired to connect and empathize with somebody, the more specific detail the person gives, the more we relate to it.

Greg Larson:

The right details, for sure. I see this as a problem in a lot of literary fiction and literary nonfiction, it's like this self-congratulating scene building. The reader doesn't always need to see everything. If a couple of characters are in, say an arcade or something, a person generally knows what an arcade looks like, but if you're zeroing the focus into a specific detail, make it for a reason. Otherwise, it's just showing off, it's just literary gymnastics, but that's more into the craft of writing, not the preparation as much.

Ben Guest:

Right. I agree 100% with that. The keys in the early stages and the beginning stage is what's the experience, compressed timeframe, greatest change. And who's the audience. And within that audience, who's my ideal reader, and what's the impact I want this to have on my ideal reader?

Greg Larson:

What's the impact to, I want this to have on my life too? That's an important part that I think a lot of people miss. You should be selfish in this part of the planning process. Again, we're focused on non-fiction. Yeah, you might be writing a non-fiction book to teach people something specific, maybe it's prescriptive nonfiction, whatever it may be, but you need to have a selfish goal for yourself. If it is getting speaking events, if it is having more newsletter subscribers, having a larger following on social media, whatever it is, that's an important aspect to this process because you need to have an incentive to keep going that is somewhat selfish.

Ben Guest:

With Clubbie, what was your side of that? And what was the audience side of that?

Greg Larson:

For the most part, I was blind writing Clubbie. I learned through air, I didn't know how to do a lot of this stuff yet, but as far as audience goes, I had a specific idea in my mind of the audience, I was like, "My audience member... " Because with baseball, I could've gone so deep into statistics that it would've alienated certain people. But then if I would've assumed too much ignorance on the part of my reader, it would've alienated even more people. So it was like my ideal reader knows what an earned run average is and what a batting average is, but they don't know the significance of say a wins above replacement or the more obscure metrics. That was the knowledge level that I was working with. It's a baseball fan who knows earned run average and batting average, and that's the way I wrote it. But as far as like my specific goals, I was not articulating those to myself just yet. I don't think I was as nuanced in my planning process at that point.

Ben Guest:

When you started your outline for Clubbie, did you have a theme in mind in the way that in a piece of fiction writing generally we'll create a theme?

Greg Larson:

Yeah. The theme was Minor League Baseball players are taking advantage of and look at what that world is like. And I wrote, and I outlined, "Oh, this is what their love life is like," that's one chapter. "This is how the Dominicans are treated. And then this is how they handle the off season," that kind of stuff. And I wrote a rough draft in that way, and it was just boring, it was impersonal, it just didn't work. But then when I started writing it more as narrative nonfiction, as a memoir, I did this weird thing where I had two Google Documents, a Google Document on the right with just chaos notes. I chopped up some of the old boring pieces that I thought might be useful, threw it into this note document. I had little fragments of little notes that I would scribble in class and I would type it up in there. And then on the other Word document, I had, it wasn't even a draft, I was just starting to write what was happening in the story. I wasn't writing prose, I was basically just writing a summary like, "I drive down to Florida, I meet with the team, I meet X, Y, and Z here." And I kept doing that. And then what happened was, it naturally just turned into prose, and I didn't try to, but as I went on more and more, I was like, "Oh, I know what the dialogue is here because I have the notes on this side of the screen and I know what's happening." And then eventually, by the end of it, I was just writing a full draft. By the time I got finished with that full draft, I could go back to the beginning and then say, "Oh, I know what this prose is supposed to be." So it was almost like writing half of a draft and then going back and writing the first half of the draft, and that seemed to work.

Ben Guest:

Yeah, there's a phrase I heard once, I think it was something like jumping out of an airplane and sewing the parachute together as you're in the air. And that's what you did, just jumping in, putting it together. And by the time you get to the end, now I can go back and finish the beginning.

Greg Larson:

Yeah. Dude, I hadn't thought of this, I love that metaphor as well, but I hadn't thought this metaphor or this analogy before until like the last week. We were talking about therapy before we started recording. In the first draft, when I'm in a therapy session, I'm just saying whatever comes to my mind and I'm making connections that my unconscious mind is making that I don't recognize. Then it's my therapist who says, "Here's what's happening here." In the first draft, I'm the crazy person in the chair just making connections, just trying to trust my gut intuition, free association as much as possible. And then in the second draft and the third draft, I'm like the therapist where because now I'm outside of it, I can see what I was trying to do much better. It's that realization helped me recognize or more easily trust my instincts in the first draft.

Ben Guest:

That is so great, because one of the things that the therapist is doing, the professional is doing ,is finding patterns and helping you see patterns, right?

Greg Larson:

Yes.

Ben Guest:

So now, the patient side of it is we're just throwing stuff out there, so go back to writing, we're throwing stuff on the page, thoughts, ideas, quotes, fragments, and then therapist side of it is, we're finding the through line. And sorry, as I've mentioned on previous podcasts, there's some construction going above my apartment, so you may hear random little banging sounds and so forth. Let's jump over to the fiction side. One of the things I did over the pandemic was I wrote a screenplay, and it's a zombie movie, because in some ways, COVID, the pandemic, it was like living in a zombie apocalypse where this thing is spreading and coming and so forth. And the theme that I came up with was the idea that “Everything changes.” True in normal times, and obviously even more so when you're living through a pandemic. Everything changes. You had a normal life and now everything has changed. The reason I'm mentioning that in the outlining process is I have that phrase, everything changes. That's my theme for this screenplay that I'm going to write. And now I have that at the top of my outline, because I want that either consciously or subconsciously, to just be working as I'm doing my planning, because that's the heart of the piece and everything needs to be in service of reaching that. And it may never be explicitly stated in the screenplay, it may never be explicitly stated in theoretical movie, it should all be residing there in the intent of the writer.

Greg Larson:

Yeah. I like that idea. I've heard a guy I really look up to, he did the same thing where he would write, his word was “Vulnerability”. He just wrote “Vulnerability” on a Post-It and he always had it on his computer so that everything you write, if it wasn't in service of that word, he would cut it out no matter how good it was, and he had a lot of success in his book.

Ben Guest:

And the book was eight pages long.

Greg Larson:

“I'm not telling you guys anything about myself.” My version of that is I have a question that I'm trying to answer. Like the novel that I'm working on right now, my question that I'm trying to answer is, how do our relationships with our parents impact our romantic relationships? Because sometimes I hesitate to start with an explicit theme, because then it's almost like I'm starting with an answer before I even ask a question. I want to just explore the question and see and surprise myself in a certain way too. It's scary because I don't always know where the book is going and it surprises me, but it also makes it more exciting.

Ben Guest:

I love that. One thing that I want to be clear about is, there are many different paths up the mountain. As many authors as there are, that's as many paths up the mountain to completing your work that there are. And so I like this idea of just comparing our different processes. And again, in the detail, people will find things that they can relate to. So I love the idea of start with a question and then you're going to start working towards answering that question. I need to have the structure of knowing where this is going, and it sounds like for you, you don't need to have that.

Greg Larson:

Oh, I'm at least trying not to. The novel that I'm writing, I think I've technically tried it. This is the third time and I didn't really know that this is really the third time. But looking back in the past, I can see, "Oh, I tried to tell this in some way." The first time I tried it was four years ago and I legit had no plan whatsoever. I was just writing words and then what came out were just fragments of chaos and it wasn't a book, it was just like a series of thoughts. The difference now is that I have a rough idea of the ending and I have a rough idea of this question that I'm trying to answer. But what I'm allowing myself to have is to discover new characters along the way. That's been a biggest one where these two characters are in a summer camp and I think it's all about this love story of these two characters in the summer camp falling in love for the first time. But then lo and behold, that the man of this camp actually becomes a really prominent figure, even though I didn't realize this was going to happen, and so now I'm not going to say, "Well, it wasn't in the outline, so I'm not going to have this character." It's like, "No, I discovered this guy and he needs to be a fully developed character as well." That's been the biggest difference in this iteration of this novel."

Ben Guest:

That's fantastic because that's also part of the magic, that's the spooky side of it. Right? So if we're talking actionable items, I guess for the listeners, for people that are interested in writing a piece of nonfiction memoir, a biography, what have you, think of the most transformative time in your life and the lesson or lessons you learned in that time. From there, think about, how would you like if you were to write this experience down, if you were to create a piece of art around this experience, how would you like that to impact someone else, someone you don't even know, someone reading this story? What's the takeaway you want them to have? And then from there, think about, what are your goals for writing this book? And who's your ideal reader? Who are you writing for day to day? Does that cover it?

Greg Larson:

I think those are the most important questions to ask. I would call that the positioning part of the process. The questions you need to answer, ask yourself and to answer before you go into the outline process. Yeah, I think that covers it.

Ben Guest:

And then on the fiction side, and again, many different paths up the mountain, I think two ways to do it. One is to think of, "What is a theme like ‘Everything changes’ that I want to explore, that I want to process, that I want to think about? What is a question I have? How do our parents impact relationships with our romantic relationships? So what's a question I have? Now, how do I want to explore that?" One way would be to start with a theme, another way would be to start with a question outlining. How do you outline?

Greg Larson:

So for nonfiction, I'd say this applies to both prescriptive nonfiction and narrative nonfiction, but I start with brainstorming a table of contents, not even thinking about it as a table of contents, but just brainstorming the main stories and brainstorming the main lessons that I want to evoke in the book. I try to come up with a minimum of 20, and then inevitably, it's going to get condensed down and you're going to add more. But starting with 20 I think is a really good starting point. And then once you have those 20 brainstormed chapter topics, not even think about them as like chapter titles. People get obsessed with chapter titles way too early and it gets them stuck. But once you have those chapter topics, again, don't even worry about order and structure yet. I use a table in Google Docs where I have chapter topic and then I have either a thesis or a question that I'm trying to answer in the chapter, as in like, "What overall point am I trying to make in this chapter/what question am I trying to answer in this chapter?" And then I come up with a hook. Your mileage may vary, but I've never seen anybody successfully write a nonfiction book after coaching 100 plus people who has basically written their book in the outline. I haven't seen anyone do it successfully yet. I'm sure somebody does, but just like sentence fragments in the outline. What's the hook? Story of getting fired from a FinTech company. Boom, that's the hook. I'll remember that when I go to write it. And then I do, "What are the stories or anecdotes or examples in the chapter that I want to tell? What are the points I want to make? What are the actions I want the reader to take based on those points that I'm making?" Those are the biggest ones. Most people just tell stories and they don't have any takeaways. An even smaller percentage of people have stories and then have the takeaways. An even tiny percentage stories, takeaways, and actions to take. That's the key to writing excellent nonfiction, I think.

Ben Guest:

And can you say a little bit more about the actions to take that focus-

Greg Larson:

Yeah, for sure. That's exactly what we're doing in this podcast, it's a perfect example of it. We're talking abstractly, but then you're saying, "Okay, based on what we said, here's the action you should take." An example, I helped my friend edit his book that's written for young men in their 20s who are trying to find their way in life after college. And he had a story about him moving to Austin and not knowing how to make friends, and that's an interesting story. But then he said, the takeaway is that you need to treat everybody as though they're a friend until they prove otherwise. Boom, there's a takeaway. There's an aphorism that they can use. And then he had an action for them to take, he's like, "Create a customer management system for friends, and here's how I do it, here's how you can do it." So he had a story, a takeaway, and an action, a specific action for them to take. And what I've found is that people who write nonfiction, more often than not, they think that the things that they know are way more useless than they are. It's like if you're an expert in something, even if you're expertise is in your own life, you're more often going to dismiss what you know just because you are an expert. It seems obvious and easy to you because you're the expert, but to a reader or a listener, you have to lay it out explicitly and that's valuable.

Ben Guest:

I love it. And when you're doing this kind of outline, you personally, pen-paper, computer, note cards, what?

Greg Larson:

I do it on a Google Drive document, and I have a template that I use that I can just repeat. I can copy and paste these 10 tables so that all of the segmenting off is already filled in. It's like, "Oh, there's a box for stories and there's a box for points." That kind of thing. That's how I use it. And then I write the draft. I'm writing my current novel on Legal Pad, but I would never write nonfiction on Legal Pad, I think, I don't know why exactly, but a narrative story I'd write on the-

Ben Guest:

Nice. So just to recap. One of the advantages actually with non-fiction is, basically, you know the ending. If you've selected this transformative moment in your life or you and I have both done ghost writing and co-authoring someone else's life, the transformative event or events. But generally, you want to keep it as tight as possible, the lesson they learned from that or the life lesson, I guess. If you know that, you know how it ends, you know what you want to communicate, that's then going to help you when you come up with the chapter topics. Because something that takes a detour off that main road probably doesn't need to go any further.

Greg Larson:

Probably so, but I want to make an important distinction here. The difference between a memoir and prescriptive nonfiction, a memoir is explicitly a narrative, it's nonfiction written with all the tenets of good fiction, character, scene, plot, all that stuff. That's a different beast in a certain way. And that should be constrained in a timeframe. Whereas prescriptive nonfiction, which is the type of... like how-to books, self-help books, business books, that kind of thing, they're going to have memoir elements of stories and stuff, but it doesn't need to be as constrained, it just needs to be constrained by the topic. So those stories can be plucked from all different aspects of your life, they both serve different purposes.

Ben Guest:

The prescriptive writing, like you're saying, there's lots of room for lots of different types of topics and lots of different stories and lots of different examples, and the overall theme can be as narrow or as wide as you want to make it.

Greg Larson:

Yes, exactly.

Ben Guest:

Okay. If we jump over to fiction, so if I go back to my zombie apocalypse screenplay, so now I have my theme, “Everything changes.” So now what I do is, I'm going to come up with the characters, and I'm going to come up with their backstory, the kind of music they like, are they an introvert or an extrovert? Do they have a lot of friends or just a few friends? What's their favorite movie? Just some information. When I then do act one, act two, act three, I have something to generate why this person is doing this thing in this moment.

Greg Larson:

Do you use character diamonds?

Ben Guest:

No. Talk to me about that.

Greg Larson:

It's a screenwriting tool that I've been trying to use for fiction. I'm not super familiar with it, but in general, a character diamond, it's like a four-pointed diamond, the same kind of diamond you'd see on a ski hill, like double diamond. A character diamond, so you have at the very top of a diamond like the point of a four points diamond you might see on a ski hill. At the very top is the primary trait of the character or their North Star, what they want more than anything else in the world. And then opposing it is their mask, the version of themselves that they show the world that they would probably never admit to themselves. And then on the other side, on the horizontal points, on one end is their non-negotiable, the hill that they're willing to die on, and then on the other end is their fatal flaw. And theory behind it that I've learned or that I'm trying to understand more completely is that, the more opposed each of those points in the diamond are, the more strong that character will be. An example, like Han Solo, I guess. Han Solo's primary trait, he's he's a maverick cowboy space bounty hunter. That's his primary trait. And then his shadow or his mask is that he's an emotionless swashbuckler. His fatal flaw, I think that he is money hungry and that he would do anything for money. But the hill he's willing to die on is his friends. So it's like these things are somewhat opposed. I'm sure I'm fucking up the vertical diamond's points, but we're learning as we go here. But the more opposed these things are, the stronger the character. I'm trying to understand that relative to fiction writing.

Ben Guest:

Right. That is a great framework because storytelling almost always involves conflict, internal conflict and external conflict. So that's a great way to figure out both the character's internal conflict and then find things that are going to spark external conflict. I think the most important is deciding what your character really wants, because that's usually going to drive the actions they take, and that will eventually drive the conflict. David Mamet says each scene should be, what does the hero want? Why doesn't she get it? What happens next? That until the character gets what they want, which doesn't happen until the very end of the story, you're always going to have forward plot momentum.

Ben Guest:

So to use our Star Wars idea, Luke Skywalker, in the first Star Wars, Luke Skywalker wants to leave home and go on an adventure. He gets that, not necessarily in the way that he was initially thinking, but that's eventually what he gets by the end of the film.

Greg Larson:

The details for these characters, their backgrounds and stuff, sometimes you just have to know that as the author, but your reader doesn't have to know that. How do you discern which goes in and which is just is for you?

Ben Guest:

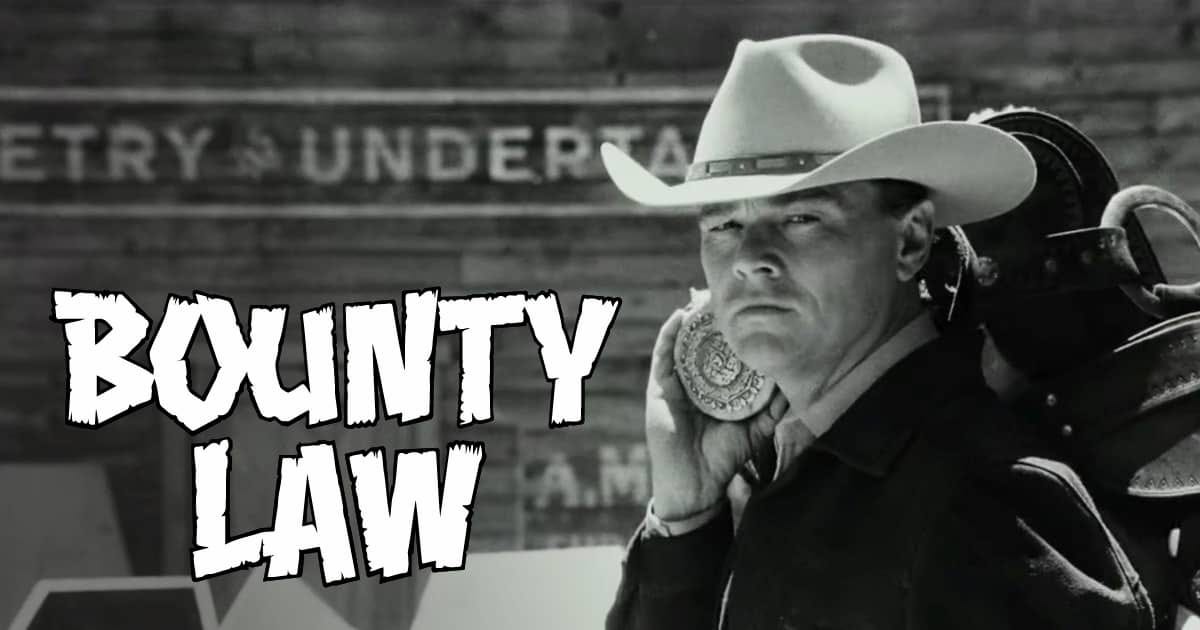

I saw an interview with Tarantino about Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. And in that film, Leonardo DiCaprio's character is on a '50s Western TV show called Bounty Law. It's not really important in terms of when you're watching the film, they just cut to it a few times. Tarantino said he wrote six episodes of Bounty Law just so he would know exactly what this show is that this character had been the lead actor on that the movie is not even about. It's not about the lead actor. It's not about Leonardo being in Bounty Law, it's about 10 years later when Leonardo is losing his career. And I'm sure there are other authors that just have a really light sketch.

So for me, I like to be somewhere in the middle. I don't want to spend all this time thinking about, what did they major in college? And there are certain things like music or your favorite movie that if you know that, that's what you need to know to sketch the character out. So for me, I have like an iceberg that has a third underneath, one third above and two thirds underneath, something like that at maybe.

Greg Larson:

Got you. But you keep those things to yourself for the most part.

Ben Guest:

Yeah. I would say the ratio of what you know versus what you reveal is... Again, sorry for the hammering, I don't know, one to six probably. So, I know this character's favorite movie is Aladdin, there's a one in six chance that at some point that's going to be mentioned somewhere or referenced somewhere in the story. What about character in terms of nonfiction or in terms of memoir?

Greg Larson:

For my most recent memoir, I did a lot of interviews with the guys that were going to be characterized in the book. It's an interesting balance to play. The characters are real people and so in the first draft, I had to think about it in sociopathic terms, like, I'm not going to think about the ramifications of telling these stories on the real people, I'll think about that in the edit. And so the first draft, or I should say the first draft of my memoir as an actual narrative memoir, I had stuff in there about people that I eventually cut out because I was like, "This is wildly inappropriate." Inside Clubhouse stuff, even beyond inside baseball, it was just like, it might have ruined marriages kind of stuff. And I was like, "This is just not worth it." But at the same to time, I was looking at it through the lens of, what did I see? Anything that I see or hear is mine to own from then on, and anything that I could discover online, I would try to figure out as much as possible. I don't know, man, it's a hard question to answer because you're confined by who somebody really is and who somebody was as you saw of them at that time. I didn't do it real consciously.

Ben Guest:

Right. And that's one of the things you always have to think about with real people is, "This is my perception of one side of them or one side of their mask even, and this thing I'm creating is going to live "forever" I'm putting that in quotation marks, "in the world." So I think that tactic that you mentioned is exactly right. In the planning stages when it's just you and you, 100% honesty and openness about everything. Right now, it's just stuff you're throwing on the metaphorical page and it doesn't ever need to go further than that. But early on, I think it actually until you get to the editing phase, honesty is the best pilot, and the more open and the more honest, the better.

Greg Larson:

Yes. You're going to be honest throughout the entire process, but it's just a matter of how much you reveal.

Ben Guest:

Yeah. That's a better way to put it, 100%. Now we've got our char, we've got our theme, we have our question, we have our audience, we have our goals, we have our characters.

Greg Larson:

I was curious, actually you mentioned the three act structure in screenwriting, and that's another one of those things I'm like, "Man, how much does that apply to novel writing?" Where did you learn the three act structure and how did you start implementing it?

Ben Guest:

Sure. The most famous, I guess in interpretation is Joseph Campbell, The Hero's Journey. So act one would be leaving home, Luke Skywalker's aunt and uncle are killed and he flies off to the stars. And then act two is discovering the new world and ends with the lowest point. So in Star Wars, it's when Obi-Wan is killed. And then act three is triumph. Usually you get what you wanted, but not in the way you wanted, you changed as a person and you bring peace back to the land or whatever it is. The Matrix fits that perfectly where Neo, at the end of act one is when Neo leaves the Matrix, is pulled out of the Matrix.

Ben Guest:

Then act two is learning this new world, and the end of act two is when Morpheus is captured, it's the low point. And then act three is the triumph. But I like to make it even simpler and so I go back to David Mamet, who said, "Act one is you get your character up a tree, act two is you light the tree on fire. And so it's just each scene should lead into the next scene. And generally, the scene should lead into the next scene because the character isn't getting something. So if we go back to Mamet's idea of up a tree, tree on fire, then the character is going to reach a stumbling block and then a character's going to reach a much bigger stumbling block. Those are your ends of act one and act two. So let me ask you, does that translate into fiction writing and memoir writing? I'm trying to think in my own mind now?

Greg Larson:

If I'm doing it well. That's the thing, is I think, well, two things, did you learn that from what's called The Hero with a Thousand Faces? I don't know.

Ben Guest:

Yeah. That's the Joseph Campbell book. I haven't read that book, but there's plenty of work that's been done off of it. Yeah, 100%.

Greg Larson:

But did you find that framework somewhere else?

Ben Guest:

Yeah. Just online, there's a bunch of stuff on the Hero's Journey and there's a circle diagram that you just follow the circle in terms of the events that can happen in that type of story.

Greg Larson:

As far as memoir, does that framework hold up for memoir? Here's some mistakes that I made when writing both my memoirs is that I wasn't thinking about it in terms of those really tightly defined storytelling elements. I was just trying to write a story interestingly, but I didn't even... A fatal flaw with literary fiction and literary nonfiction is that they focus more on character than story, which they're not mutually exclusive, but I was focusing more on the internal transformations of the characters, which is interesting, but it didn't always have... When you read upmarket fiction, you can tell that each chapter is like the cliff hanger at the end of an episode of a really great TV show and it keeps you going more, and more and that's not an accident. And it's a formula that I'm trying to learn, but I don't even know how to learn it exactly yet. I'm just trying to write this novel that I'm writing, I'm just trying to write each scene in a way that somebody transforms in some little way at the end of it, and that we get a little bit closer to what I think the ending is without wasting the reader's time and trying to do it as beautifully as possible.

Ben Guest:

So to that idea then the impetus to keep going is every scene I read in Greg's book, I'm learning a little something because there's a little nugget of truth of a life lesson in there.

Greg Larson:

Well, that would be more for prescriptive nonfiction, but if I'm thinking of a narrative of a memoir or a novel, I don't know that there even needs to be a life lesson, it's just the character develops or the plot advances a little bit farther. But with prescriptive nonfiction, ideally it would be some kind of life lesson, because a reader isn't reading a self-help book or a how-to book to watch a character develop. They're reading it so that their own characters can develop oddly enough. And so in order to do that, you have to help them transform at the end of the chapter. I'd never made that connection before, but a prescriptive nonfiction book is a book in which the hero is the reader.

Ben Guest:

Oh, that's deep. That's fantastic. And the hero's going on a journey, the reader's going on a journey hopefully, or they're going to take steps to go on a journey. Oh, I like that. I'm working on a memoir right now about coaching basketball, coaching high school in the states and then professionally "overseas" in Namibia, in Southern Africa. So what I try to do there is each scene, each chapter should have enough forward plot momentum that it makes you want to read the next chapter, very, very light cliff hangers. That's how I think about it in memoir writing that there needs to be, why is the reader going to turn a page? What are your thoughts about it with memoir?

Greg Larson:

I look back at my old work and I cringe because I would do it so differently now, but what I tried to do with my most recent memoir was end each chapter in a way that... It was like I would be in scene for most of the chapters. We're in the clubhouse, we're on the field and I'm describing details in a way that you can actually put yourself there. And at the end of each chapter, I would try to zoom out a little bit and not say, "This is what it meant." And when I was there, I would do something more like, I can find an example here.

Ben Guest:

I love it. Available at fine independent bookstores near you.

Greg Larson:

That's exactly right.

Ben Guest:

Or even better, signed by the author online.

Greg Larson:

That's right. At clubbiebook.com. So this is the end of chapter 11, where I am in the middle of two seasons. It's the off season and we spend a lot of time in my off season home in South Carolina with my girlfriend and our relationship troubles and it's like, "Am I going to go back to baseball or am I going to stay in South Carolina?" Well, there's another half of the book, so we know what's going to happen. So we're in scene in the house for most of the chapter. And then at the very end, I decided that I'm going to go back and there's these final couple of paragraphs where I zoom out and I'll read a few sentences.

Greg Larson:

And just like that, I packed my things into the caddy for the drive north, Nicole and I renewed our lease so I was coming right back there once the season finished. We said goodbye to each other just like we had so many times before. Aberdeen had been just a memory.

So now I'm zooming back a little bit.

I never thought I'd actually return there anymore than I'd returned to my youth, but I looked forward to the season in a certain way, like when you do the same things over and over again expecting something to be fundamentally different, because it's always the next meal, the next fuck, the next Christmas that will finally make you happy, the next baseball season, because this is all you know how to do. You don't ask the sun, why you orbit, you just orbit. You let the gravitational waves of the baseball season pull you in and you surrender yourself happily. You slap on your faded, blue stretch, fit BP cap with the orange cursive “A”on the crown and you drive your Cadillac from one single story, brick rambler to another somewhere just off the I-95 corridor in Maryland.

And so there's this zooming out that I think I wasn't consciously doing that, but that was how I would give the reader a cliffhanger. It was like, scene, scene, scene, zoom out for a little bit of, "Oh, here's the meaning of what happened," without saying like, "Here's the meaning of what happened." And I think that kept some momentum going, even though I didn't realize that's what I was doing.

Ben Guest:

That's such a great framework, Greg. So to my mind, the best storytellers out there are the folks at This American Life, the radio program, their framework is exactly that, scene, scene, scene, what's the bigger meaning behind this? Scene, scene scene, what's the bigger... And that's exactly what it is. So that I think is a beautiful way to end the chapter and to plug's into people's naturally wanting to make connections, hear a story and understand what the greater connection is, the greater meaning.

Greg Larson:

Yes. And I found that readers were actually upset or at least inquisitive about the parts where I didn't zoom out and provide the greater meaning. And I wanted to be like, "Well, just look at the action and discern for yourself." But they wanted my guidance as the author, which totally makes sense. Again, I can look back and see places that I would've done it differently.

Ben Guest:

What chapter was that the end of?

Greg Larson:

Chapter 11.

Ben Guest:

So in your outline, what do the chapter 11 outline look like?

Greg Larson:

If I recall correctly, I did not have anything like, "Oh, expand out at the very end of the chapters." No. I think it was just literally, I said off season, and then I wrote a bunch of fragmented details of come back to South Carolina, find mess, Nicole and I argue, like that kind of stuff. It was chaos us in a certain way, but that's how I think about it. It's like writing a book is taking like the chaos of my ideas into the order of-

Ben Guest:

Right. Back to our therapy analogy, randomness of this, this and this, okay, where's the pattern in it? The next thing that I do, if I go back to my screenplay and my act. So act one, if we do the zombie movie, act one is when the zombies start taking over the world and this father and his two teenage kids have to find shelter. That's the end of act one. And then the end of act two is the father has a medical condition, I gave him meningitis, and he needs to have a shot of penicillin to save him. So now the kids are going to have to leave the shelter that they sought out. So just act one, act two. And then in act three, the father dies, but the daughter who is the main character comes to accept that everything changes. And then what I'm going to do is plot out scene by scene. Scene one is going to start in the chemistry lab at the high school, scene two is going to be the hallway in the locker room, scene three is going to be the wrestling mat. And then I have the characters who are in that scene and the point of that scene. And now to your point about the diagram, the character diamond, on the left hand side of the outline for each scene, vertically I write each of the characters in that scene once. And then vertically on the right side, and I think this is the key, and this is going back to something you said really early on in this conversation, on the right side, I write down what is the emotion I want the audience to be feeling in this scene. Do I want them laughing, scared, nervous, whatever? All of that translates to any kind of storytelling, I think, except maybe prescriptive in terms of what is the emotional feeling, what is the emotion I want the audience to have at this moment?

Greg Larson:

Do you know how many scenes you're going to have in each act? Do you set that aside beforehand or know an ideal?

Ben Guest:

No. Generally, for me, it's like 10, 10 and 10. It's like a third, a third, a third, but depending on again, many pass, many stories. The other thing especially with fiction writing, so not screenplay writing, but fiction writing and memoir, it's also like the story's going to tell you how to tell it, because we haven't even into non-linear storytelling, but In some ways as you're working through the story, it will also reveal to you the way in which you should tell that story, right?

Greg Larson:

I like that. I like the screenwriting tenets because screenwriting has to be way more succinct than these other forms of writing, you have to be totally dialed in. That dialed-in process, I don't even start that until the editing phase. In the drafting phase, I'm just like, have a rough idea and fucking bang it out, but I want to use that in my editing process because I can be too slip shot with like, "Oh, what exact points or emotion are we trying to evoke?"

Ben Guest:

I'm just trying to think of this, the memoir I'm working on now how I outline that. So it's 21 chapters, and you said Clubbie was 20 chapters, right?

Greg Larson:

Yep.

Ben Guest:

So similar number of chapters. And then I know the events that are happening in chronological order, first game of the playoffs is a chapter. And then maybe just the two or three key moments I want to hit in that chapter. And that's it.

Greg Larson:

Are you going off of like a journal or anything like that? Yeah, that's invaluable. I honestly, I don't know how people would write a memoir without having something like that.

Ben Guest:

What's really funny Greg is, the book covers two basketball seasons, and I kept a journal the second season. And the second season, everybody, all my early readers, they're all like, "Man, the second half of the book just moves in a good way." And I'm like, "Yeah, it's because I had so much of that iceberg to work from. And the first half I'm trying to remember conversations from five years ago."

Greg Larson:

Did you have a lot of summary in the first half of the book or were you still able to build-

Ben Guest:

The biggest thing, actually I was working on this morning, is just going back, and this goes back to screenplay writing of the idea of show don't tell. I was just doing a lot of telling and now basically I'm just going back and recreating dialogue to make it more in the moment.

Greg Larson:

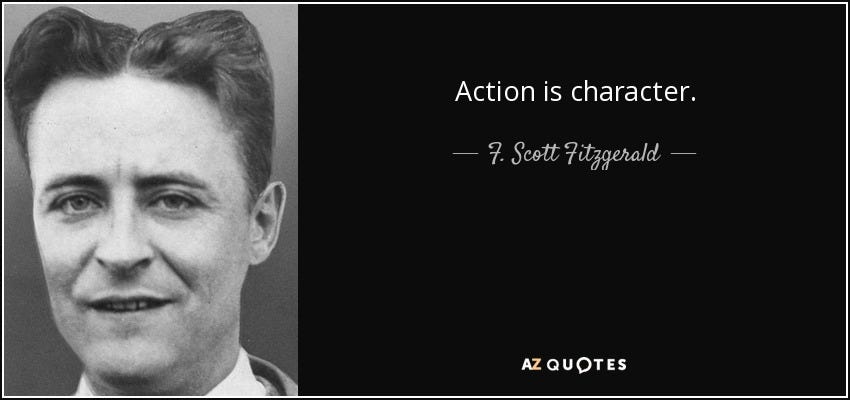

Show versus tell is an important comparison. This thing that I learned in school that was really helpful distinction on that was scene versus summary of scene building of a story with dialogue and summary of here's what happened, "I went to the store that day and I bought apple juice," that kind of stuff. And another one, this is getting more into the craft of actually storytelling, but action is character is one of the biggest ones that I've stuck with, that one of my teachers taught me from F. Scott Fitzgerald. That's been a big one, don't tell the reader who somebody else is, just show it to them.

Ben Guest:

If you have to tell the reader, you’re a shitty storyteller. You should be able to show the character by the action.

Greg Larson:

I want to talk about one part of the planning process that I haven't mentioned yet that is so important that a lot of people screw up. I teach people how to do this and I still screw it up. You can have all this stuff right and you still... Forget about writing a great book, but not even finishing your first draft ever. You can do all of this right and just not write your words because of anxiety is getting in the way and because of all kinds of stuff. The way I think about it, you need a writing plan, accountability and a reward system in order to get your book regardless of what genre you're working in.

Greg Larson:

The way I think about it is this, a writing plan, how many words per day are you going to write? And are you going to be writing on only weekdays? Are you going to be writing only on weekends? Are you going to do seven days a week? That's your writing plan? Where are you going to write? What time of day are you going to write? And actually put in it in your Google or Outlook calendar, whatever it be. And so you have a specific word count that you have to reach every single week, for example. For me, it's two pages per weekday, so 10 pages per week.

Greg Larson:

My goal is two pages a day that turns into 10 written pages per week. That's my writing plan. And then the accountability, this is where a lot of people mess up, you have to have accountability in order to finish your book, I think. My accountability is that I send a video of the 10 pages I've written to my friend, my business partner, Alex, every Friday at 6:30 PM to prove that I've actually written a book. And those little details matter a lot because then all of a sudden, I have somebody that's like, I don't know if he even cares or would be disappointed, but I would be disappointed if I didn't have it to send to him.

Greg Larson:

And then the rewards and punishment, if I do that every week, I reward myself. For me, I go get barbecue or I go to a buffet or something. And then the punishment is I send him $100 if I don't do it. I think a lot of authors mess that up because those are the workday technicalities of actually getting your words down on the page. I don't know if it's going to turn into an amazing book, but I know that it's going to get me a finished book, and that's way better than an unfinished book.

Share this post